-

-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 10

Commit

This commit does not belong to any branch on this repository, and may belong to a fork outside of the repository.

- Loading branch information

Showing

1 changed file

with

320 additions

and

0 deletions.

There are no files selected for viewing

This file contains bidirectional Unicode text that may be interpreted or compiled differently than what appears below. To review, open the file in an editor that reveals hidden Unicode characters.

Learn more about bidirectional Unicode characters

| Original file line number | Diff line number | Diff line change |

|---|---|---|

|

|

@@ -5,7 +5,327 @@ | |

|

|

||

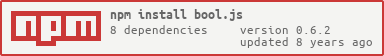

| [](https://npmjs.com/packages/bool.js) | ||

|

|

||

| # Getting Started with bool.js | ||

|

|

||

| This is the very absolute beginners guide you'll need to understand how you can start using bool.js | ||

|

|

||

| ## Prerequisites | ||

|

|

||

| * **Node.js v4.0.0 or later**: No, you can't escape from this, as our incredibly modern API uses the latest features of the ES6 standard, such as classes and that stuff. | ||

| * **Git 1.9.0 or later**: Recommended for having control in every aspect of your project as it rapidly grows. | ||

|

|

||

| ## Let's begin | ||

|

|

||

| > _TL;DR_ | ||

| > | ||

| > You can do it in two ways: the hard one or the easy one. The first implies cloning our boilerplate, taking your time to deeply know the workspace and begin the project by . | ||

| ### The hard one | ||

|

|

||

| Start by cloning the boilerplate, | ||

|

|

||

| ```bash | ||

| git clone https://github.com/booljs/booljs-boilerplate.git sample | ||

| ``` | ||

|

|

||

| Once you get it, open the folder where it is located and delete last | ||

|

|

||

| ```bash | ||

| cd sample | ||

| rm -rf .git | ||

| git init | ||

| ``` | ||

|

|

||

| Then, initialize the project and install bool.js | ||

|

|

||

| ```bash | ||

| npm init | ||

| npm install -S bool.js | ||

| ``` | ||

|

|

||

| Finally, modify line 2 in `index.js`, should look like this: | ||

| ```js | ||

| var booljs = require('bool.js'); | ||

| ``` | ||

|

|

||

| And fill out the base namespace of your application (yes, we use namespaces, I'll tell you about this later) in line 5. For example, if your API is being located in http://api.awesomeapp.com, your namespace would be something like: | ||

| ```js | ||

| booljs('com.awesomeapp.api').run(); | ||

| ``` | ||

|

|

||

| `index.js` will end up this way: | ||

|

|

||

| ```js | ||

| 'use strict'; | ||

| var booljs = require('bool.js'); | ||

|

|

||

| // Here is where magic happens | ||

| booljs('com.awesomeapp.api').run(); | ||

| ``` | ||

|

|

||

| Now, you're ready to start. | ||

|

|

||

| ### The easy one | ||

|

|

||

| Simple as this: install bool.js in your computer through npm. | ||

|

|

||

| ```bash | ||

| sudo npm install -g bool.js | ||

| ``` | ||

|

|

||

| Then, use the CLI to start the application. Fill out the namespace (yes, we use namespaces, I'll tell you about this later) and the directory where your project is being created. In case you don't mention a path, CLI will use the one you're being located. | ||

|

|

||

| ```bash | ||

| bool create <namespace> [dir] | ||

| ``` | ||

|

|

||

| Follow the instructions and you're done. | ||

|

|

||

| ## First run | ||

|

|

||

| > Basic code comes with an example of: configuration files, found in… configuration (D'Oh!) folder, controllers, DAO (or business logic, if you think in a better name than ours, let us know [here](mailto:[email protected])), models, and plugins. | ||

| We prepared a _kitten free_ sample using a dog store, where you can see how to create a resource. Just type `node index.js` and you're in. | ||

|

|

||

| ## Dissecting workspace structure | ||

|

|

||

| > TL;DR | ||

| > | ||

| > Bool.js code are plain functions with at least one parameter: `app`, which is a reference to the namespace-based components, from where you can instantiate your code. Those return the objects you can use everywhere in your application. They can be controllers, DAO, models, routes and plugins. | ||

| > | ||

| > Models and routes are very strict in their structure, as they're the interfaces to connect the rest of the architecture and follow the specifications of the database and web server drivers. The others (unless specified) are designed up to your criteria, following certain code styles and conventions. | ||

| > | ||

| > Finally, depending on how you name your files, they will be referenced as CamelCase classes in the namespace structure. | ||

| ### Namespaces | ||

|

|

||

| If javascript is not your first programming language, you'll probably know the concept of namespaces. I mean, they exist almost everywhere: Python, Java, C++/C#… even PHP use them, altough you didn't know it. However, if you are not familiar to them, here's the best introduction you'll ever find about what a namespace is. | ||

|

|

||

| > Namespaces are a hierarchical way to arrange code, dividing it into... what? You said it'd be easy. Let's start again. | ||

| Have you ever used sorted your music in folders? First you sort them by artist, them by albums and finally (if needed) by CD numbers. Then, you look up your favorite songs easier than having all them merged in one place, in a way like: `artist/album/cd1/my_favourite_song.mp3`. | ||

|

|

||

| Well, that kind of sorting can be made in code too! We call it namespaces, and are simple as this: sort code into similar kinds of behaviours, so if you'd like to know where is the (for example): Dog's controller, you'll find it into the controllers module, into the application. Then, look up in a way like this: `application.controllers.Dog`. Pretty similar, huh? | ||

|

|

||

| In bool.js there are seven essential kinds of components: configuration files, controllers, business logic code (better known as DAO), models, routes, plugins and views. | ||

|

|

||

| All of them come from a single base object, defined as a parameter in the modules' header. | ||

|

|

||

| #### File conventions | ||

|

|

||

| Bool.js uses the filenames to call classes in the application skeleton. Here are the basic rules: | ||

|

|

||

| 1. A class is called like the filename, with its first letter capitalized. | ||

| 2. If a `_` character is found, is taken as a word separator, and is processed as another word, giving each word the same treatment of rule 1. | ||

|

|

||

| ##### Examples | ||

|

|

||

| `controllers/dog.js` gets transformed into `controllers.Dog` | ||

| `models/artist_albums` gets transformet into `models.ArtistAlbums` | ||

|

|

||

| And so on… | ||

|

|

||

| ### Modules: what are them? | ||

|

|

||

| A module is basically a function containing executable code, which passes parameters referencing the application's other components through namespaces, as well as other parameters: database drivers, libraries, etc. You can recognize them as code files into the following folders: `controllers`, `dao`, `plugins`, `models` and `routes`. | ||

|

|

||

| They consist in three parts: the header definitions, the code body and the returning section. Now, let's examine very carefully each one of these. | ||

|

|

||

| #### Header section | ||

|

|

||

| This is the part of code defining what is going to be exported as a component. Consists on a `use strict` header, because we like to be strict, but safe; and a `module.exports` sentence returning a function. The function takes at least one parameter: can be called whatever you want, but we recommend to call it `app`, so you will know it is about the application's status. | ||

|

|

||

| ```js | ||

| 'use strict'; | ||

|

|

||

| module.exports = function (app) { | ||

|

|

||

| }; | ||

| ``` | ||

|

|

||

| #### Definitions section | ||

|

|

||

| Essentially is the part where you define your variables. Here you are free to do whatever you want, with some recommendations. | ||

|

|

||

| 1. Don't use `require`. The reason to make bool.js namespace-based is precisely to avoid making complicated calls to files. If you have a recurring piece of code you want to use, then create a module of it in the `plugins` folder, and then you can call it instantiating the component `app.plugins.WhateverYouCanCallItPlugin`. | ||

| 2. Never declare variables or running code outside code body, before or after the function definition. This is an anti-pattern as can turn your code non-stateless, and eventually cause troubles. | ||

| 3. When you are importing application components, remember to point constructors: then, in the code body, instantiate them, so you'll mantain your code stateless. | ||

|

|

||

| A good example of achieving this, is the definition section of a controller. | ||

|

|

||

| ```js | ||

| 'use strict'; | ||

|

|

||

| module.exports = function (app) { | ||

| var Dog = app.dao.Dog | ||

| , Json = app.views.Json | ||

| , Uuid = app.plugins.Uuid; | ||

|

|

||

| } | ||

| ``` | ||

|

|

||

| #### Code body | ||

|

|

||

| Here comes the fun part. The code body is exactly that: an object (array, function, whatever), where you put all your skills and imagination to make it work. Generally, is a literal object (yes, a moustache `{}` containing a bunch of functions and fields) where executable code is located, and is returned by the function to be used in other parts of the application. Depending on the component type, you must follow some interfaces for these functions, like controllers, but this doesn't always happen. | ||

|

|

||

| Here is an example of a code body, from the controller: | ||

|

|

||

| ```js | ||

| return { | ||

| list: function (req, res, next) { | ||

| var dog = new Dog() | ||

| , json = new Json(); | ||

|

|

||

| json.promise(dog.list(req.query), res, next); | ||

| }, | ||

| create: function (req, res, next) { | ||

| var dog = new Dog() | ||

| , json = new Json(); | ||

|

|

||

| json.promise(dog.create(req.body), res, next); | ||

| }, | ||

| update: function (req, res, next) { | ||

| var dog = new Dog() | ||

| , json = new Json(); | ||

|

|

||

| dog.update(req.params.id, req.body, function (err, data) { | ||

| if(err) return next(err); | ||

| json.standard(data); | ||

| }); | ||

| } | ||

| }; | ||

| ``` | ||

|

|

||

| Altough we use to return functions in a literal object, a good (and sometimes cleaner) choice might be returning a reference to `this` and declaring functions as fields of the function. This is something like the following example. | ||

|

|

||

| ```js | ||

| this.list = function (req, res, next) { | ||

| var dog = new Dog() | ||

| , json = new Json(); | ||

|

|

||

| json.promise(dog.list(req.query), res, next); | ||

| }; | ||

|

|

||

| this.create = function (req, res, next) { | ||

| var dog = new Dog() | ||

| , json = new Json(); | ||

|

|

||

| json.promise(dog.create(req.body), res, next); | ||

| }; | ||

|

|

||

| this.update = function (req, res, next) { | ||

| var dog = new Dog() | ||

| , json = new Json(); | ||

|

|

||

| dog.update(req.params.id, req.body, function (err, data) { | ||

| if(err) return next(err); | ||

| json.standard(data); | ||

| }); | ||

| }; | ||

|

|

||

| return this; | ||

| ``` | ||

|

|

||

| This way is often used in mongoose models, because we are returning an Schema instance, and into it, we declare handy functions and mongoose plugins. | ||

|

|

||

| ### The router stuff | ||

|

|

||

| **Router components** are _modules_ that contain an array of routes that must be deployed by the web server driver. A route is a literal object (`{}`), defining the necessary elements to describe a path to be deployed by the web server's router. | ||

|

|

||

| The collection of elements include the path, denoted by `url` field; the HTTP verbose method, `method` field; the handler, a controller identified by `action` field, and that must comply the web server's specifications, but is generally a function with two parameters: `request` and `response`. | ||

|

|

||

| Depending on middleware loaded to be implemented, other fields, known as policies, could be included in the router definition. For example: bool.js default's web server implementation, express.js, includes a middleware to output CORS headers. | ||

|

|

||

| ```js | ||

| 'use strict'; | ||

|

|

||

| module.exports = function (app) { | ||

| var dog = new app.controllers.Dog(); | ||

|

|

||

| return [ | ||

| { | ||

| method: 'get', | ||

| url: '/dog', | ||

| action: dog.list | ||

| }, | ||

| { | ||

| method: 'get', | ||

| url: '/dog/:id', | ||

| action: dog.find | ||

| } | ||

| ]; | ||

| }; | ||

| ``` | ||

|

|

||

| #### Policy types: mandatory and omittable. | ||

|

|

||

| None of the policies are required to be included in the route's definition. However, middleware are required to specify whether they can be activated or disabled. Mandatory policies are those which need to exist in the route's definition with an specific value to activate the middleware in the route. Contrary to first ones, omittable policies are those which being declared in the route's definition disable the behaviour of the middleware for an specific route. | ||

|

|

||

| I apply `booljs-cors` and `booljs-oauth` plugins to an API. First one defines a Middleware with mandatory policies, while OAuth plugin is omittable. In that case, if I define these routes: | ||

|

|

||

| ```js | ||

| { | ||

| method: 'get', | ||

| url: '/dog/:id', | ||

| action: dog.find, | ||

| cors: true | ||

| }, | ||

| { | ||

| method: 'get', | ||

| url: '/dog', | ||

| action: dog.list | ||

| public: true | ||

| } | ||

| ``` | ||

|

|

||

| OAuth will execute in first route, because its disable policy `public: true` doesn't appear. In the second case, because CORS type is mandatory, won't set headers, however, it won't require a Bearer authorization, because we've declared the disable policy. | ||

|

|

||

| ### Controllers | ||

|

|

||

| Less strict than routers, but still following the server's specifications, controllers define the point where the web requests are received and start gathering information to process its behaviour. Their code body must return an object containing functions. | ||

|

|

||

| Each function passes two essential parameters: the `request` information, as well as the server's `response`. Depending on the server's implementation, some other parameters (such as `next`) can be passed. | ||

|

|

||

| If included in the server's implementation (default's implementation includes one), you can apply views, which are prebuilt responses for API calls. | ||

|

|

||

| Also, is recommended that routers don't reference more than one controller, because this will cause multiple instances of them, and it's recommended to have just one of them. To avoid issues, load references in code body, not in definitions section. | ||

|

|

||

| Finally, avoid combining business logic code (field validations, complex joining operations). To achieve that goal, you must code these operations in DAO components: they are the main point to the back-end of the API, and should be carefully documented for project's developers or other's projects which use your project's resources via calling them in API requires. | ||

|

|

||

| ```js | ||

| 'use strict'; | ||

|

|

||

| module.exports = function (app) { | ||

| var Dog = app.dao.Dog | ||

| , Json = app.views.Json; | ||

|

|

||

| return { | ||

| list: function (req, res) { | ||

| new Dog().list(req.query, function (err, data) { | ||

| if(err) { | ||

| Json.error(err, res); | ||

| } | ||

| Json.standard(data, res); | ||

| }); | ||

| }, | ||

| find: function (req, res, next) { | ||

| /* | ||

| * booljs-express' Json view includes a promises processor and | ||

| * handles errors via next | ||

| */ | ||

| new Json().promise(new Dog().find(req.params.id), res, next); | ||

| } | ||

| }; | ||

| } | ||

| ``` | ||

|

|

||

| ### DAO | ||

|

|

||

| DAO components are the most important part of the bool.js architecture: serve as projects' internal API, as well as being the separation point between API's front-end and back-end. Behind this point you can't handle web anything related to web, socket or any kind of external operations, however you got access to data origins, validation tools and utilities and greater resources. | ||

|

|

||

| Code body must return an object. Unless specified by a requiring plugin (such as `booljs-oauth`), the structure is completely free. However, we keep recommending you to use the code conventions for definition section. | ||

|

|

||

| As we told you before, you can use a lot of resource, specially those coming from the namespace `app.utils`: they are utilities you declare from native libraries in node.js, and aren't defined as plugins, so they work as expected in their original documentation. | ||

|

|

||

| ## FAQ | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||