English | 简体中文

stream is part of go-zero, but a few people asked if fx (it’s called fx in go-zero) can be used separately. But I recommend you to use go-zero for many more features.

Java developers should be very impressed with Stream API in Java, which greatly improves the ability to handle data collections.

int sum = widgets.stream()

.filter(w -> w.getColor() == RED)

.mapToInt(w -> w.getWeight())

.sum();The idea of Stream is to abstract the data processing into a data stream and return a new stream for use after each process.

The most important step is to think through the requirements before writing the code, so let's try to put ourselves in the author's shoes and think about the flow of the component. First of all, let's put the underlying implementation logic aside and try to define the stream function from scratch.

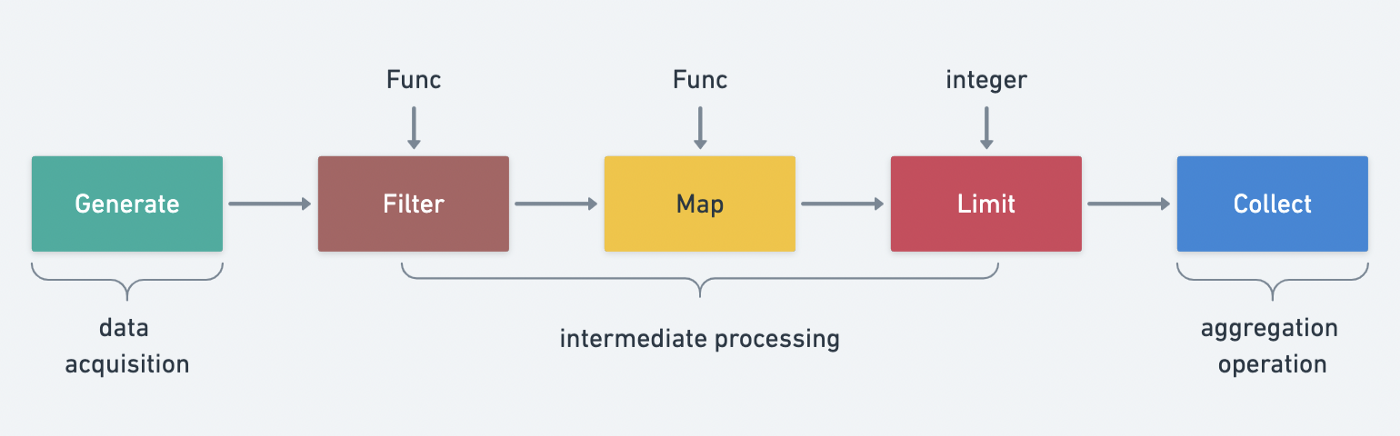

Stream's workflow is actually part of the production-consumer model, and the whole process is very similar to the production process in a factory.

- creation phase/data acquisition (raw material)

- processing phase/intermediate processing (pipeline processing)

- aggregation stage/final operation (final product)

The API is defined around the three life cycles of a stream.

In order to create the abstract object stream, it can be understood as a constructor.

We support three ways of constructing streams: slicing conversion, channel conversion, and functional conversion.

Note that the methods in this phase are normal public methods and are not bound to the stream object.

// Create stream by variable parameter pattern

func Just(items ... .interface{}) Stream

// Create a stream via channel

func Range(source <-chan interface{}) Stream

// Create stream by function

func From(generate GenerateFunc) Stream

// Concatenate a stream

func Concat(s Stream, others . . Stream) StreamThe operations required in the processing phase often correspond to our business logic, such as conversion, filtering, de-duplication, sorting, and so on.

The API for this phase is a method that needs to be bound to a Stream object.

The following definition is combined with common business scenarios.

// Remove duplicate items

Distinct(keyFunc KeyFunc) Stream

// Filter item by condition

Filter(filterFunc FilterFunc, opts ... . Option) Stream

// Grouping

Group(fn KeyFunc) Stream

// Return the first n elements

Head(n int64) Stream

// Returns the last n elements

Tail(n int64) Stream

// Convert objects

Map(fn MapFunc, opts . . Option) Stream

// Merge items into slice to create a new stream

Merge() Stream

// Reverse

Reverse() Stream

// Sort

Sort(fn LessFunc) Stream

// Works on each item

Walk(fn WalkFunc, opts ... . Option) Stream

// Aggregate other Streams

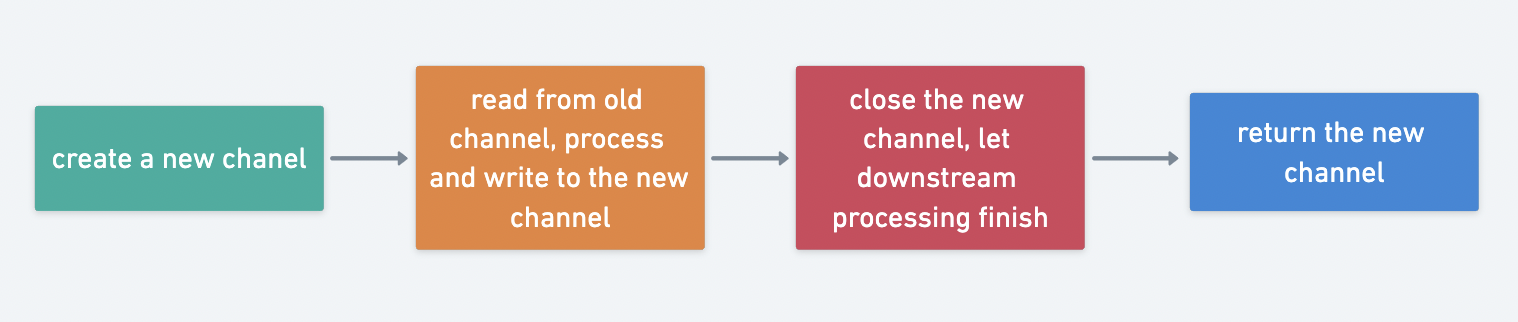

Concat(streams ... . Stream) StreamThe processing logic of the processing phase returns a new Stream object, and there is a basic implementation paradigm here.

The aggregation phase is actually the result of the processing we want, e.g. whether it matches, count the number, traverse, etc.

// Check for all matches

AllMatch(fn PredicateFunc) bool

// Check if at least one match exists

AnyMatch(fn PredicateFunc) bool

// Check for all mismatches

NoneMatch(fn PredicateFunc) bool

// Count the number of matches

Count() int

// Clear the stream

Done()

// Perform an operation on all elements

ForAll(fn ForAllFunc)

// Perform an operation on each element

ForEach(fn ForEachFunc)After sorting out the requirements boundaries of the component, we have a clearer idea of what we are going to implement with Stream. In my perception, a real architect's grasp of requirements and their subsequent evolution can be very precise, and this can only be achieved by thinking deeply about the requirements and penetrating the essence behind them. By replacing the author's perspective to simulate the entire project build process, learning the author's thinking methodology is the greatest value of our learning open source projects.

Well, let's try to define the complete Stream interface and functions.

The role of the interface is not just a template, but also to use its abstraction capabilities to build the overall framework of the project without getting bogged down in the details at the beginning, to quickly express our thinking process through the interface concisely, to learn to develop a top-down thinking approach to observe the whole system from a global perspective, it is easy to get bogged down in the details at the beginning.

rxOptions struct {

unlimitedWorkers bool

workers int

}

Option func(opts *rxOptions)

// key generator

// item - the element in the stream

KeyFunc func(item interface{}) interface{}

// filter function

FilterFunc func(item interface{}) bool

// object conversion function

MapFunc func(intem interface{}) interface{}

// object comparison

LessFunc func(a, b interface{}) bool

// traversal function

WalkFunc func(item interface{}, pip chan<- interface{})

// match function

PredicateFunc func(item interface{}) bool

// perform an operation on all elements

ForAllFunc func(pip <-chan interface{})

// performs an operation on each item

ForEachFunc func(item interface{})

// execute operations on each element concurrently

ParallelFunc func(item interface{})

// execute the aggregation operation on all elements

ReduceFunc func(pip <-chan interface{}) (interface{}, error)

// item generation function

GenerateFunc func(source <-chan interface{})

Stream interface {

// Remove duplicate items

Distinct(keyFunc KeyFunc) Stream

// Filter item by condition

Filter(filterFunc FilterFunc, opts . . Option) Stream

// Grouping

Group(fn KeyFunc) Stream

// Return the first n elements

Head(n int64) Stream

// Returns the last n elements

Tail(n int64) Stream

// Get the first element

First() interface{}

// Get the last element

Last() interface{}

// Convert the object

Map(fn MapFunc, opts . . Option) Stream

// Merge items into slice to create a new stream

Merge() Stream

// Reverse

Reverse() Stream

// Sort

Sort(fn LessFunc) Stream

// Works on each item

Walk(fn WalkFunc, opts ... . Option) Stream

// Aggregate other Streams

Concat(streams ... . Stream) Stream

// Check for all matches

AllMatch(fn PredicateFunc) bool

// Check if there is at least one match

AnyMatch(fn PredicateFunc) bool

// Check for all mismatches

NoneMatch(fn PredicateFunc) bool

// Count the number of matches

Count() int

// Clear the stream

Done()

// Perform an operation on all elements

ForAll(fn ForAllFunc)

// Perform an operation on each element

ForEach(fn ForEachFunc)

}The channel() method is used to get the Stream pipeline properties, since we are dealing with the interface object in the implementation, we expose a private method to read out.

// Get the internal data container channel, internal method

channel() chan interface{}With the functional definition sorted out, next consider a few engineering implementations.

Chain calls, the builder pattern used to create objects can achieve the chain call effect. In fact, Stream implements a similar chain effect on the same principle, creating a new Stream to return in each call.

// Remove duplicate items

Distinct(keyFunc KeyFunc) Stream

// Filter item by condition

Filter(filterFunc FilterFunc, opts . . Option) StreamThe pipeline can be understood as a storage container for data in Stream. In go we can use channel as a pipeline for data to achieve the effect of asynchronous non-blocking when Stream chain calls perform multiple operations.

Data processing is essentially processing the data in the channel, so to achieve parallel processing is simply to consume the channel in parallel, using the goroutine and WaitGroup can be very convenient to achieve parallel processing.

core/fx/stream.go

The implementation of Stream in go-zero does not define an interface, but the logic is the same when it comes to the underlying implementation.

To implement the Stream interface we define an internal implementation class, where source is of type channel, to emulate the pipeline functionality.

Stream struct {

source <-chan interface{}

}Create stream via channel

func Range(source <-chan interface{}) Stream {

return Stream{

source: source,

}

}It's a good habit to create streams in variable parameter mode and close the channel when you're done writing.

func Just(items ... .interface{}) Stream {

source := make(chan interface{}, len(items))

for _, item := range items {

source <- item

}

close(source)

return Range(source)

}Stream creation by function

func From(generate GenerateFunc) Stream {

source := make(chan interface{})

threading.GoSafe(func() {

defer close(source)

generate(source)

})

return Range(source)

}Because it involves external calls to function parameters, the execution process is not available so you need to catch runtime exceptions to prevent panic errors from being transmitted to the upper layers and crashing the application.

func Recover(cleanups ... . func()) {

for _, cleanup := range cleanups {

cleanup()

}

if r := recover(); r ! = nil {

logx.ErrorStack(r)

}

}

func RunSafe(fn func()) {

defer rescue.Recover()

fn()

}

func GoSafe(fn func()) {

go Runsage(fn)

}Splice other Streams to create a new Stream, calling the internal Concat method method, the source code implementation of Concat will be analyzed later.

func Concat(s Stream, others . . Stream) Stream {

return s.Concat(others...)

}Because the function parameter KeyFunc func(item interface{}) interface{} is passed in, it means that it also supports custom distincting according to business scenarios, essentially using the results returned by KeyFunc to achieve distincting based on a map.

The function arguments are very powerful and provide a great deal of flexibility.

func (s Stream) Distinct(keyFunc KeyFunc) Stream {

source := make(chan interface{})

threading.GoSafe(func() {

// It's a good habit for channels to remember to close

defer close(source)

keys := make(map[interface{}]lang.PlaceholderType)

for item := range s.source {

// Custom de-duplication logic

key := keyFunc(item)

// If the key does not exist, write the data to a new channel

if _, ok := keys[key]; !ok {

source <- item

keys[key] = lang.

Placeholder }

}

})

return Range(source)

}Use case.

// 1 2 3 4 5

Just(1, 2, 3, 3, 4, 5, 5).Distinct(func(item interface{}) interface{} {

return item

}).ForEach(func(item interface{}) {

t.Log(item)

})

// 1 2 3 4

Just(1, 2, 3, 3, 4, 5, 5).Distinct(func(item interface{}) interface{} {

uid := item.(int)

// Special de-duplication logic for items greater than 4, so that only one item > 3 is retained

if uid > 3 {

return 4

}

return item

}).ForEach(func(item interface{}) {

t.Log(item)

})The actual filtering logic is delegated to the Walk method by abstracting the filtering logic into a FilterFunc and then acting on the item separately to decide whether to write back to a new channel based on the Boolean value returned by the FilterFunc.

The Option parameter contains two options.

- unlimitedWorkers No limit on the number of concurrent processes

- workers Limit the number of concurrent processes

FilterFunc func(item interface{}) bool

func (s Stream) Filter(filterFunc FilterFunc, opts . . Option) Stream {

return s.Walk(func(item interface{}, pip chan<- interface{}) {

if filterFunc(item) {

pip <- item

}

}, opts...)

}Example usage.

func TestInternalStream_Filter(t *testing.T) {

// keep even numbers 2,4

channel := Just(1, 2, 3, 4, 5).Filter(func(item interface{}) bool {

return item.(int)%2 == 0

}).channel()

for item := range channel {

t.Log(item)

}

}walk means walk, here it means to perform a WalkFunc operation on each item and write the result to a new Stream.

Note here that the order of the data in the channel of the new Stream is random because the internal concurrent mechanism is used to read and write data asynchronously.

// item element in item-stream

// The pipe-item is written to the pipe if it matches the condition

WalkFunc func(item interface{}, pipe chan<- interface{})

func (s Stream) Walk(fn WalkFunc, opts . .Option) Stream {

option := buildOptions(opts...)

if option.unlimitedWorkers {

return s.walkUnLimited(fn, option)

}

return s.walkLimited(fn, option)

}

func (s Stream) walkUnLimited(fn WalkFunc, option *rxOptions) Stream {

// Create a channel with a buffer

// default is 16, channel with more than 16 elements will be blocked

pipe := make(chan interface{}, defaultWorkers)

go func() {

var wg sync.WaitGroup

for item := range s.source {

// All elements of s.source need to be read

// This also explains why the channel is written last and remembered to finish

// If it is not closed, it may lead to leaks and blocking

// Important, not assigning a value to val is a classic concurrency trap, and is used later in another goroutine

val := item

wg.Add(1)

// Execute the function in safe mode

threading.GoSafe(func() {

defer wg.Done()

fn(item, pipe)

})

}

wg.Wait()

close(pipe)

}()

// return a new Stream

return Range(pipe)

}

func (s Stream) walkLimited(fn WalkFunc, option *rxOptions) Stream {

pipe := make(chan interface{}, option.workers)

go func() {

var wg sync.WaitGroup

// Control the number of concurrent processes

pool := make(chan lang.PlaceholderType, option.workers)

for item := range s.source {

// Important, not assigning a value to val is a classic concurrency trap, used later in another goroutine

val := item

// will block if the concurrency limit is exceeded

pool <- lang.

// This also explains why the channel is written last and remembered to finish

// If you don't close it, it may cause the concurrent thread to keep blocking and lead to leaks

wg.Add(1)

// Execute the function in safe mode

threading.GoSafe(func() {

defer func() {

wg.Done()

// Read the pool once to release a concurrent location after execution is complete

<-pool

}()

fn(item, pipe)

})

}

wg.Wait()

close(pipe)

}()

return Range(pipe)

}Use case.

The order of returns is randomized.

func Test_Stream_Walk(t *testing.T) {

// return 300,100,200

Just(1, 2, 3).Walk(func(item interface{}, pip chan<- interface{}) {

pip <- item.(int) * 100

}, WithWorkers(3)).ForEach(func(item interface{}) {

t.Log(item)

})

}Put in map by matching item.

KeyFunc func(item interface{}) interface{}

func (s Stream) Group(fn KeyFunc) Stream {

groups := make(map[interface{}][]interface{})

for item := range s.source {

key := fn(item)

groups[key] = append(groups[key], item)

}

source := make(chan interface{})

go func() {

for _, group := range groups {

source <- group

}

close(source)

}()

return Range(source)

}n is greater than the actual dataset length, all elements will be returned

func (s Stream) Head(n int64) Stream {

if n < 1 {

panic("n must be greather than 1")

}

source := make(chan interface{})

go func() {

for item := range s.source {

n--

// The value of n may be greater than the length of s.source, you need to determine if it is >= 0

if n >= 0 {

source <- item

}

// let successive method go ASAP even we have more items to skip

// why we don't just break the loop, because if break,

// this former goroutine will block forever, which will cause goroutine leak.

// n==0 means that source is full and can be closed

// Since source has met the condition, why not just break and jump out of the loop?

// The author mentions preventing goroutine leaks

// Because each operation will eventually create a new Stream, and the old one will never be called

if n == 0 {

close(source)

break

}

}

// The above loop jumped out of the loop, which means n is greater than the actual length of s.source

// still need to show the new source closed

if n > 0 {

close(source)

}

}()

return Range(source)

}Example usage.

// return 1,2

func TestInternalStream_Head(t *testing.T) {

channel := Just(1, 2, 3, 4, 5).Head(2).channel()

for item := range channel {

t.Log(item)

}

}It is interesting to understand the implementation of the Ring in order to ensure that the last n elements are obtained using the Ring data structure.

// ring slicing

type Ring struct {

elements []interface{}

index int

lock sync.Mutex

}

func NewRing(n int) *Ring {

if n < 1 {

panic("n should be greather than 0")

}

return &Ring{

elements: make([]interface{}, n),

}

}

// Add elements

func (r *Ring) Add(v interface{}) {

r.lock.Lock()

defer r.lock.Unlock()

// Write the element to the slice at the specified location

// The remainder here achieves a circular writing effect

r.elements[r.index%len(r.elements)] = v

// Update the next write position

r.index++

}

// Get all elements

// Keep the read order the same as the write order

func (r *Ring) Take() []interface{} {

r.lock.Lock()

defer r.lock.Unlock()

var size int

var start int

// When there is a circular write situation

// The start read position needs to be decimalized, because we want the read order to be the same as the write order

if r.index > len(r.elements) {

size = len(r.elements)

// Because of the cyclic write situation, the current write position index starts with the oldest data

start = r.index % len(r.elements)

} else {

size = r.index

}

elements := make([]interface{}, size)

for i := 0; i < size; i++ {

// Read the remainder in a circular fashion, keeping the read order the same as the write order

elements[i] = r.elements[(start+i)%len(r.elements)]

}

return elements

}To summarize the advantages of ring slicing.

- Supports automatic scrolling updates

- Memory saving

Ring slicing enables old data to be overwritten by new data when the fixed capacity is full, and can be used to read n elements after the channel due to this feature.

func (s Stream) Tail(n int64) Stream {

if n < 1 {

panic("n must be greather than 1")

}

source := make(chan interface{})

go func() {

ring := collection.NewRing(int(n))

// Read all elements, if the number > n ring slices can achieve new data over old data

// ensure that the last n elements are obtained

for item := range s.source {

ring.Add(item)

}

for _, item := range ring.Take() {

source <- item

}

close(source)

}()

return Range(source)

}So why not just use a len(source) length slice?

The answer is to save memory. Any data structure that involves a ring type has the advantage of saving memory and allocating resources on demand.

Example usage.

func TestInternalStream_Tail(t *testing.T) {

// 4,5

channel := Just(1, 2, 3, 4, 5).Tail(2).channel()

for item := range channel {

t.Log(item)

}

// 1,2,3,4,5

channel2 := Just(1, 2, 3, 4, 5).Tail(6).channel()

for item := range channel2 {

t.Log(item)

}

}Element conversion, internally done by a concurrent process to complete the conversion operation, note that the output channel is not guaranteed to be output in the original order.

MapFunc func(intem interface{}) interface{}

func (s Stream) Map(fn MapFunc, opts . . Option) Stream {

return s.Walk(func(item interface{}, pip chan<- interface{}) {

pip <- fn(item)

}, opts...)

}Example usage.

func TestInternalStream_Map(t *testing.T) {

channel := Just(1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2).Map(func(item interface{}) interface{} {

return item.(int) * 10

}).channel()

for item := range channel {

t.Log(item)

}

}The implementation is relatively simple, and I've thought long and hard about what scenarios would be suitable for this method.

func (s Stream) Merge() Stream {

var items []interface{}

for item := range s.source {

items = append(items, item)

}

source := make(chan interface{}, 1)

source <- items

close(source)

return Range(source)

}Reverses the elements of the channel. The flow of the reversal algorithm is

- Find the middle node

- The two sides of the node start swapping two by two

Notice why slices are used to receive s.source when it is fetched? Slices are automatically expanded, wouldn't it be better to use arrays?

In fact, you can't use arrays here, because you don't know that Stream writing to source is often done asynchronously in a concurrent process, and the channels in each Stream may change dynamically.

func (s Stream) Reverse() Stream {

var items []interface{}

for item := range s.source {

items = append(items, item)

}

for i := len(items)/2 - 1; i >= 0; i-- {

opp := len(items) - 1 - i

items[i], items[opp] = items[opp], items[i]

}

return Just(items...)

}Example usage.

func TestInternalStream_Reverse(t *testing.T) {

channel := Just(1, 2, 3, 4, 5).Reverse().channel()

for item := range channel {

t.Log(item)

}

}The intranet calls the official slice package sorting scheme, just pass in the comparison function to implement the comparison logic.

func (s Stream) Sort(less LessFunc) Stream {

var items []interface{}

for item := range s.source {

items = append(items, item)

}

sort.Slice(items, func(i, j int) bool {

return less(items[i], items[j])

})

return Just(items...)

}Example usage.

// 5,4,3,2,1

func TestInternalStream_Sort(t *testing.T) {

channel := Just(1, 2, 3, 4, 5).Sort(func(a, b interface{}) bool {

return a.(int) > b.(int)

}).channel()

for item := range channel {

t.Log(item)

}

}func (s Stream) Concat(steams . .Stream) Stream {

// Create a new unbuffered channel

source := make(chan interface{})

go func() {

// Create a waiGroup object

NewRoutineGroup()

// Asynchronously read data from the original channel

group.Run(func() {

for item := range s.source {

source <- item

}

})

// Asynchronously read the channel data of the Stream to be stitched

for _, stream := range steams {

// open a concurrent process for each Stream

group.Run(func() {

for item := range stream.channel() {

source <- item

}

})

}

// Block and wait for the read to complete

group.Wait()

close(source)

}()

// return a new Stream

return Range(source)

}func (s Stream) AllMatch(fn PredicateFunc) bool {

for item := range s.source {

if !fn(item) {

// need to drain s.source, otherwise the previous goroutine may block

go drain(s.source)

return false

}

}

return true

}func (s Stream) AnyMatch(fn PredicateFunc) bool {

for item := range s.source {

if fn(item) {

// need to drain s.source, otherwise the previous goroutine may block

go drain(s.source)

return true

}

}

return false

}func (s Stream) NoneMatch(fn func(item interface{}) bool) bool {

for item := range s.source {

if fn(item) {

// need to drain s.source, otherwise the previous goroutine may block

go drain(s.source)

return false

}

}

return true

}func (s Stream) Count() int {

var count int

for range s.source {

count++

}

return count

}func (s Stream) Done() {

// Drain the channel to prevent goroutine blocking leaks

drain(s.source)

}func (s Stream) ForAll(fn ForAllFunc) {

fn(s.source)

}func (s Stream) ForEach(fn ForEachFunc) {

for item := range s.source {

fn(item)

}

}The core logic is to use the channel as a pipe and the data as a stream, and to continuously receive/write data to the channel using a concurrent process to achieve an asynchronous non-blocking effect.

The basis for this efficiency comes from three language features.

- channel

- concurrency

- functional programming

go-zero: https://github.com/zeromicro/go-zero

If you like or are using this project to learn or start your solution, please give it a star. Thanks!